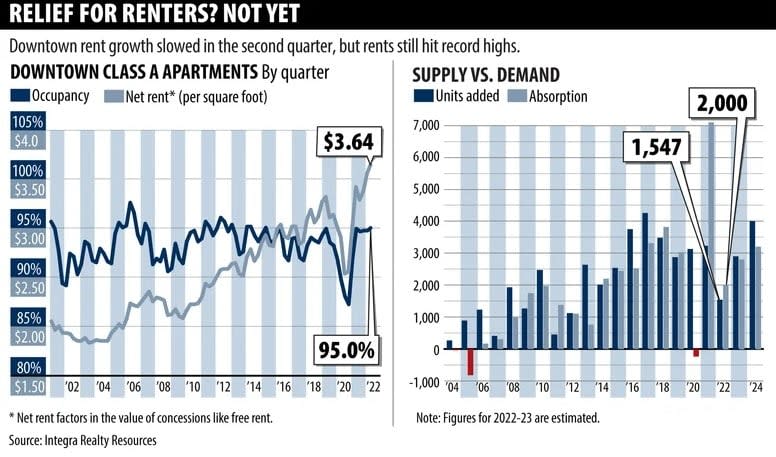

If you’re apartment hunting in downtown Chicago, this qualifies as good news in an inflationary economy: Rents are still rising, but not as much as they were. The net rent at high-end, or Class A, downtown apartment buildings rose to $3.64 per square foot in the second quarter, setting a record, according to the Chicago office of Integra Realty Resources, a consulting and appraisal firm. That’s up 6.7% from a year earlier, but it represents a meaningful moderation in the downtown market, which is recovering from whiplash after plunging in the early days of the pandemic and soaring to new heights over the past year. Rent growth has slowed from the first quarter, when the Class A net rent was up 19.1% from a year earlier, according to Integra.

It’s still a landlord’s market, even as prospects for the economy dim amid high inflation, rising interest rates and a slumping stock market. New buildings are filling up quickly. The downtown occupancy rate hit 95.2% in the second quarter, its highest level in nearly a decade. Though rent increases have slowed, “it’s still very healthy growth,” said Ron DeVries, senior managing director in Integra’s Chicago office. He expects downtown rents to rise 5% to 7% over the next 12 months. Demand for apartments depends on the local job market, which is strong. When downtown employers hire, many of their new employees choose to rent apartments nearby.

But the COVID-19 pandemic turned the downtown market upside down in 2020, as many younger professionals moved in with their parents. New hires from out of state delayed their plans to move to the city and worked remotely instead. Occupancies dropped. Rents tumbled, and landlords were forced to offer deals to keep their buildings full. Landlords regained the upper hand last year as vaccines rolled out and the economy reopened. “We got a big boost from household growth that happened with younger tenants moving out of the house or relocating to Chicago for a job. That created kind of a shock on the demand side,” DeVries said. “That contributed to the spike” in rents, he said. “Now we’re back to normal household formation.”

The market for Class B apartments, units in older, less expensive buildings, has cooled as well. The net Class B rent also hit a record high in the second quarter, $3.02 per square foot, up 5.2% from a year earlier, according to Integra. But that's down from an 18.7% year-over-year increase in the first quarter. Net rents include concessions like free rent. Absorption, a key measure of demand that shows the change in the number of occupied apartments, tells part of the story. Downtown absorption totaled an astonishing 7,048 units in 2021 as renters returned downtown in droves. But it has declined markedly this year, totaling just 1,446 units through the first half of the year, according to Integra. DeVries forecasts absorption of just 2,000 units for the full year and 2,800 in 2023. One reason absorption has fallen: Development slowed in the early days of the pandemic, so the supply of new apartments coming on the market today is low—just 1,547 units downtown this year. Even though demand remains strong, leasing is limited by the number of units available.

Downtown buildings that have opened this year include Millie on Michigan, a 47-story tower at 300 N. Michigan Ave. with 289 apartments, and One Chicago, with 276 units at Superior and State streets. But apartment construction has picked up, with developers expected to complete a more normal 2,900 units in 2023 and 4,000 in 2024, according to Integra. DeVries expects absorption to increase as well, totaling 2,800 units next year. Developers are especially busy in the Fulton Market District, where six projects totaling more than 1,700 units are under construction and nearly 6,000 are in planning. Last week, developers filed proposals with the city for two towers totaling 671 apartments in the neighborhood.

Fulton Market is getting crowded, but DeVries isn’t concerned about a glut there yet, saying all the units won’t come on the market at once. Developers of some projects may never get construction financing. Others might not break ground for years. “Not all of it’s going to get built,” DeVries said. “If all of it did get built, that would be a problem.” Indeed, financing new apartment high-rises has become more difficult this year as interest rates have jumped and lenders and investors have grown more cautious amid an uncertain economy. Construction could slow as a result. “There is a bit of a cooling in the lending market,” DeVries said. “I think that will keep the foot a little off the gas pedal.”